Math 416 Midterm 1 Review

So everything we have learned so far is to extend the real line to the complex plane.

Chapter 0 Calculus on Real values

Differentiation

Let be function on real line and be a real number.

Integration

Let be function on real line and be a real number.

Chapter 1 Complex Numbers

Definition of complex numbers

An ordered pair of real numbers can be represented as a complex number , where is the imaginary unit.

With operations defined as:

Modulus

The modulus of a complex number is defined as

De Moivre’s Formula

Every complex number can be written as , where is the magnitude of and is the argument of .

The De Moivre’s formula is useful for finding the th roots of a complex number.

Roots of complex numbers

Using De Moivre’s formula, we can find the th roots of a complex number.

If , then the th roots of are given by:

for .

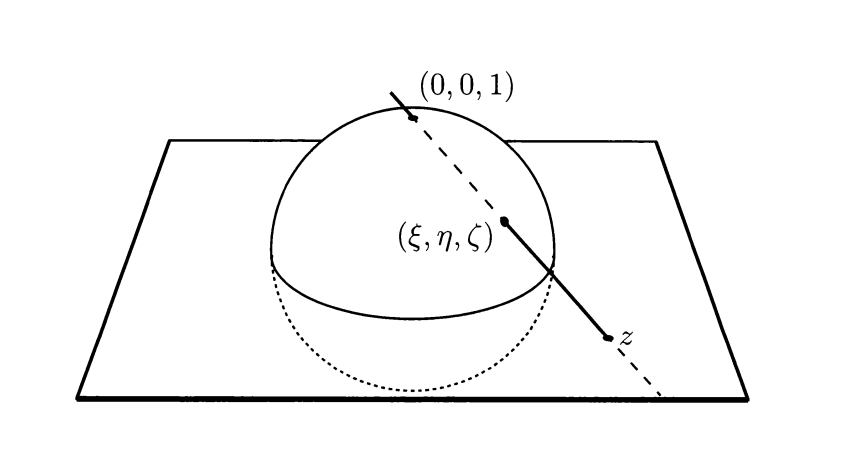

Stereographic projection

The stereographic projection is a map from the unit sphere to the complex plane .

The projection is given by:

The inverse map is given by:

Chapter 2 Complex Differentiation

Definition of complex differentiation

Let the complex plane be defined in an open subset of . (Domain)

Then is said to be differentiable at if the limit

exists.

The limit is called the derivative of at and is denoted by .

To prove that a function is differentiable, we can use the standard delta-epsilon definition of a limit.

whenever .

With such definition, all the properties of real differentiation can be extended to complex differentiation.

Differentiation of complex functions

- If is differentiable at , then is continuous at .

- If are differentiable at , then are differentiable at .

- If are differentiable at and , then is differentiable at .

- If is differentiable at and is differentiable at , then is differentiable at .

- If , where , then is differentiable at and .

Cauchy-Riemann Equations

Let the function defined on an open subset of be , where are real-valued functions.

Then is differentiable at if and only if the partial derivatives of and exist at and satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations:

On the polar form, the Cauchy-Riemann equations are

Holomorphic functions

A function is said to be holomorphic on an open subset of if is differentiable at every point of .

Partial differential operators

This gives that

If the function is holomorphic, then by the Cauchy-Riemann equations, we have

Conformal mappings

A holomorphic function is said to be conformal if it preserves the angles between the curves. More formally, if is holomorphic on an open subset of and , are two curves passing through () and intersecting at an angle , then

In other words, the angle between the curves is preserved.

An immediate consequence is that

Harmonic functions

A real-valued function is said to be harmonic if it satisfies the Laplace equation:

Chapter 3 Linear Fractional Transformations

Definition of linear fractional transformations

A linear fractional transformation is a function of the form

where are complex numbers and .

Properties of linear fractional transformations

Matrix form

A linear fractional transformation can be written as a matrix multiplication:

Conformality

A linear fractional transformation is conformal.

Three-fold transitivity

If are distinct points in the complex plane, then there exists a unique linear fractional transformation such that , , .

The map is given by

So if , are distinct points in the complex plane, then there exists a unique linear fractional transformation such that for .

Factorization

Every linear fractional transformation can be written as a composition of homothetic mappings, translations, inversions, and multiplications.

If , then

Clircle

A linear-fractional transformation maps circles and lines to circles and lines.

Chapter 4 Elementary Functions

Exponential function

The exponential function is defined as

Let , then

So we can rewrite the polar form of a complex number as

is holomorphic

Let , then , .

Trigonometric functions

Hyperbolic functions

Logarithmic function

The logarithmic function is defined as

Properties of the logarithmic function

Let , then

So we have

Power function

For any two complex numbers , we can define the power function as

Example:

Chapter 5 Power Series

Definition of power series

A power series is a series of the form

Properties of power series

Geometric series

Radius/Region of convergence

The radius of convergence of a power series is the largest number such that the series converges for all with .

The region of convergence of a power series is the set of all points such that the series converges.

Cauchy-Hadamard Theorem

The radius of convergence of a power series is given by

Derivative of power series

The derivative of a power series is given by

Cauchy Product (of power series)

Let and be two power series with radius of convergence and respectively.

Then the Cauchy product of the two series is given by

where

The radius of convergence of the Cauchy product is at least .

Chapter 6 Complex Integration

Definition of Riemann Integral for complex functions

The complex integral of a complex function on the closed subinterval of the real line is said to be piecewise continuous if there exists a partition such that is continuous on each open interval and has a finite limit at each discontinuity point of the closed interval .

If is piecewise continuous on , then the complex integral of on is defined as

Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

If is piecewise continuous on , then

Triangle inequality

Integral on curve

Let be a piecewise smooth curve in the complex plane.

The integral of a complex function on is defined as

Favorite estimate

Let be a piecewise smooth curve, and let be a continuous complex-valued function. Let be a real number such that for all . Then

where is the length of the curve .

Chapter 7 Cauchy’s Theorem

Cauchy’s Theorem

Let be a closed curve in and be a simply connected open subset of containing and its interior. Let be a holomorphic function on . Then

Cauchy’s Formula for a Circle

Let be a counterclockwise oriented circle and let be holomorphic function defined in an open set containing and its interior. Then for any in the interior of ,

Mean Value Property

Let the function be holomorphic on a disk . Then for any , let denote the circle with center and radius . Then

The value of the function at the center of the disk is the average of the values of the function on the boundary of the disk.

Cauchy Integrals

Let be a piecewise smooth curve in and let be a continuous complex-valued function on . Then the Cauchy integral of on is the function defined in by

Cauchy Integral Formula for circle :

Example:

Evaluate

Note that if we let and is inside the circle, then we can use Cauchy Integral Formula for circle to evaluate the integral.

So we have

General Cauchy Integral Formula for circle :

Example:

Evaluate

Note that if we let and is inside the circle, then we can use General Cauchy Integral Formula for circle to evaluate the integral.

So we have

Note that

So we have

Cauchy integral is a easier way to evaluate the integral.

Liouville’s Theorem

If a function is entire (holomorphic on ) and bounded, then is constant.

Finding power series of holomorphic functions

If is holomorphic on a disk , then can be represented as a power series on the disk.

where

Example:

If , find the power series of centered at .

Note that is holomorphic on and at .

So we can use the power series of centered at .

To solve this, we can simply expand and get .

So we have , , , .

So the power series of centered at is

Fundamental Theorem of Algebra

Every non-constant polynomial with complex coefficients has a root in .

Can be factored into linear factors:

We can treat holomorphic functions as polynomials.

has zero of order at if and only if for some holomorphic and .

Zeros of holomorphic functions

If is holomorphic on a disk and has a zero of order at , then , , , , and .

And there exists a holomorphic function on the disk such that and .

Example:

Find zeros of

Note that if and only if for some integer .

So the zeros of are for some integer .

The order of the zero is since and for all .

If vanishes to infinite order at (that is, ), then on the connected open set containing .

Identity Theorem

If and are holomorphic on a connected open set and for all in a subset of that has a limit point in , then for all .

Key: consider , prove on by applying the zero of holomorphic function.

Weierstrass Theorem

Limit of a sequence of holomorphic functions is holomorphic.

Let be a sequence of holomorphic functions on a domain that converges uniformly to on every compact subset of . Then is holomorphic on .

Maximum Modulus Principle

If is a non-constant holomorphic function on a domain , then does not attain a maximum value in .

Corollary: Minimum Modulus Principle

If is a non-constant holomorphic function on a domain , then does not attain a minimum value in .

Schwarz Lemma

If is a holomorphic function on the unit disk and , then .