Math401 Topic 3: Separable Hilbert spaces

Infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces

Recall from Topic 1.

Let be a measure on , or any other field you are interested in.

A function is square integrable if

space and general Hilbert spaces

Definition of

The space is the space of all square integrable, measurable functions on with respect to the measure (The Lebesgue measure).

The Hermitian inner product is defined by

The norm is defined by

The space is complete.

[Proof ignored here]

Recall the definition of complete metric space .

The inner product space is complete.

Note that by some general result in point-set topology, a normed vector space can always be enlarged so as to become complete. This process is called completion of the normed space.

Some exercise is showing some hints for this result:

Show that the subspace of consisting of square integrable continuous functions is not closed.

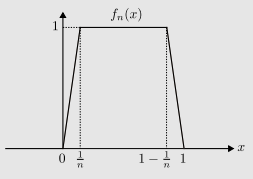

Suggestion: consider the sequence of continuous functions , where is defined by the following graph:

Show that converges in the norm to a function but the limit function is not continuous. Draw the graph of to make this clear.

Definition of general Hilbert space

A Hilbert space is a complete inner product vector space.

General Pythagorean theorem

Let be an orthonormal set in an inner product space (may not be complete). Then for all ,

[Proof ignored here]

Bessel’s inequality

Let be an orthonormal set in an inner product space (may not be complete). Then for all ,

Immediate from the general Pythagorean theorem.

Orthonormal bases

An orthonormal subset of a Hilbert space is a set all of whose elements have norm 1 and are mutually orthogonal. ()

Definition of orthonormal basis

An orthonormal subset of of a Hilbert space is an orthonormal basis of if there are no other orthonormal subsets of that contain as a proper subset.

Theorem of existence of orthonormal basis

Every separable Hilbert space has an orthonormal basis.

[Proof ignored here]

Theorem of Fourier series

Let be a separable Hilbert space with an orthonormal basis . Then for any ,

The series converges to some .

[Proof ignored here]

Fourier series in

Let .

where .

The series converges to some as .

This is the Fourier series of .

Hermite polynomials

The subspace spanned by polynomials is dense in .

An orthonormal basis of can be obtained by the Gram-Schmidt process on .

The polynomials are called the Hermite polynomials.

Isomorphism and space

Definition of isomorphic Hilbert spaces

Let and be two Hilbert spaces.

and are isomorphic if there exists a surjective linear map that is bijective and preserves the inner product.

for all .

When , the map is called unitary.

space

The space is the space of all square summable sequences.

An example of element in is .

With inner product

It is a Hilbert space (every Cauchy sequence in converges to some element in ).

Bounded operators and continuity

Let be a linear map between two vector spaces and .

We define the norm of on and .

Then is continuous if for all , if in , then in .

Using the delta-epsilon language, we can say that is continuous if for all , there exists a such that if , then .

Definition of bounded operator

A linear map is bounded if

Theorem of continuity and boundedness

A linear map is continuous if and only if it is bounded.

[Proof ignored here]

Definition of bounded Hilbert space

The set of all bounded linear operators in is denoted by .

Direct sum of Hilbert spaces

Suppose and are two Hilbert spaces.

The direct sum of and is the Hilbert space with the inner product

Such space is denoted by .

A countable direct sum of Hilbert spaces can be defined similarly, as long as it is bounded.

That is, is a sequence of elements in , and .

The inner product in such countable direct sum is defined by

Such space is denoted by .

Closed subspaces of Hilbert spaces

Definition of closed subspace

A subspace of a Hilbert space is closed if every convergent sequence in converges to some element in .

Definition of pairwise orthogonal subspaces

Two subspaces and of a Hilbert space are pairwise orthogonal if for all and .

Orthogonal projections

Definition of orthogonal complement

The orthogonal complement of a subspace of a Hilbert space is the set of all elements in that are orthogonal to every element in .

It is denoted by .

Projection theorem

Let be a Hilbert space and be a closed subspace of . Then for any can be uniquely decomposed as where and .

[Proof ignored here]

Dual Hilbert spaces

Norm of linear functionals

Let be a Hilbert space.

The norm of a linear functional is defined by

Definition of dual Hilbert space

The dual Hilbert space of is the space of all bounded linear functionals on .

It is denoted by .

You can exchange the with any other field you are interested in.

The Riesz lemma

For each , there exists a unique such that for all . And .

[Proof ignored here]

Definition of bounded sesqilinear form

A bounded sesqilinear form on is a function satisfying

- for all and .

- for all and .

- for all and some constant .

There exists a unique bounded linear operator such that for all . The norm of is the smallest constant such that for all .

[Proof ignored here]

The adjoint of a bounded operator

Let . And bounded sesqilinear form such that for all . Then there exists a unique bounded linear operator such that for all .

[Proof ignored here]

And .

Additional properties of bounded operators:

Let and . Then

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

Definition of self-adjoint operator

An operator is self-adjoint if .

Definition of normal operator

An operator is normal if .

Definition of unitary operator

An operator is unitary if .

where is the identity operator on .

Definition of orthogonal projection

An operator is an orthogonal projection if and .

Tensor product of (infinite-dimensional) Hilbert spaces

Definition of tensor product

Let and be two Hilbert spaces. and . Then is an conjugate bilinear functional on .

Let be the set of all finite lienar combination of such conjugate bilinear functionals. We define the inner product on by

The infinite-dimensional tensor product of and is the completion (extension of those bilinear functionals to make the set closed) of with respect to the norm induced by the inner product.

Denoted by .

The orthonormal basis of is . where is the orthonormal basis of and is the orthonormal basis of .

Fock space

Definition of Fock space

Let be the -fold tensor product of .

Set .

The Fock space of is the direct sum of all .

For example, if , then an element in is a sequence of functions such that .